If you happen to be going out to the mud flats below the Natural History Museum, go on a low enough tide that the eelgrass beds are really exposed, maybe a -1.0 foot tide or lower. Note the upper picture with small eelgrass patches in the mud, taken in 2018, and then compare it to the picture below, taken in 2021. This blog isn’t about eelgrass, but look how the beds have expanded! Hooray for eelgrass!

Back to my story. Californiconus (Conus) californicus, the California cone snail, can be found all over the eelgrass, something which surprised me, as I thought it was a rocky intertidal creature. Reading the reports, I found it can be found in the rocky intertidal, sand or mud, and there it was! And most of the organisms it likes to eat are found right in the mud flats, so it should be there. This snail doesn’t look like much, a greyish-brown shell about 40 mm long, in a cone shape. The lines on the shell are often obscured by the brown periostracum, or protein coat, as shown in the second figure. It has a speckled foot, and you can see the eye stalks and siphon in both figures. The siphon takes in water and tastes it, looking for the flavor of prey. It is the only cone snail found in California, but there are many brightly colored ones in the tropics. But it definitely is a mighty predator.

What you can’t see in the pictures above is the proboscis, which is below the siphon, and only extended when the prey has been found. Check out this picture—that’s the pink proboscis below the siphon:

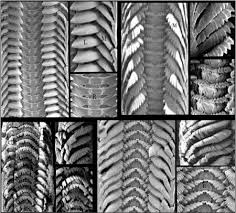

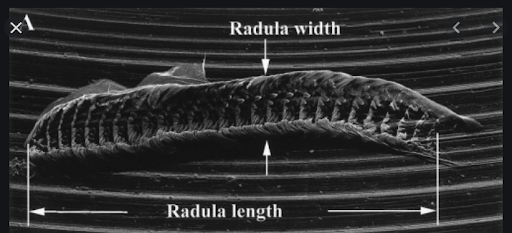

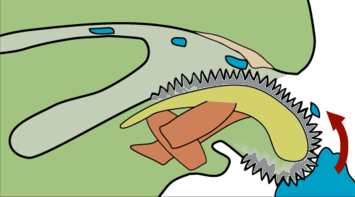

Now, about that proboscis. To digress a little, most snails have a tongue, called a radula, to scrape food from rocks, leaves, mud, etc. Radulas vary with the species of snail. Here are some pictures of radulas and how they work.

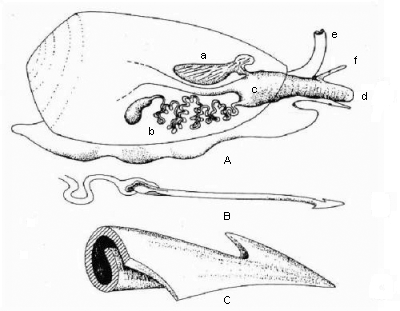

The radula in the cone snail is different. Rather than teeth in rows, each tooth is separated into a horny swirl (as in “c” below) with a dart-like tip (“b”). These darts or barbs are passed up the proboscis one at a time as needed. The interior end of each barb is attached to a venom gland which produces a protein neurotoxin called a conotoxin. Just before the barb is projected out of the proboscis, the poison is added and the barb sinks itself into the flesh of the prey, thus paralyzing it. Then the cone devours the prey and it, itself, is not bothered by the toxin.

Click on the arrow to see the cone snail in action:

So, what do these predatory snails eat? They eat a wide variety of organisms; reported food sources include 6 classes of animals in 4 different phyla. These include olive snails, jackknife clams, bent nose clams, bubble snails, dog whelks, various polychete worms and even dead fish and octopuses. All those creatures are found right in the mud at Windy Cove, so it is a good spot to search for cone snails. Here is a picture of some of the prey items I have in my collection:

Cone snails have separate sexes—but how you tell the sexes apart without dissecting them is impossible. Little is known about their reproductive cycle, but some studies have shown breeding in May, June and July. The eggs are deposited in fairly elaborate capsules on rocks, other shells and eelgrass. The larvae hatch after 10 days and swim as veligers for a time before they settle down and develop the shell.

Native Americans used cone shells as money and decoration. Today, because some of the tropical species are so toxic to humans, research is being done on ways to combat the toxin and also ways to use the toxin in medicine. I’ve included a picture of some of the more colorful cones, found mostly in the Indo-Pacific.

Sources for some pictures included in this blog:

- Eisapour M, Seyfabadi SJ, Daghooghi B (2015) Comparative Radular Morphology in Some Intertidal Gastropods along Hormozgan Province, Iran. J Aquac Res Development 6: 322. doi:10.4172/2155-9546.1000322

- Kawamura, Tomohiko; Roberts, Rodney D.; Yamashita, Yah. Radula development in abalone Haliotis discus hannai from larva to adult in relation to feeding transitions. Fisheries Science. 21 Dec. 2001

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Snail_radula_working.png